December 14, 1922

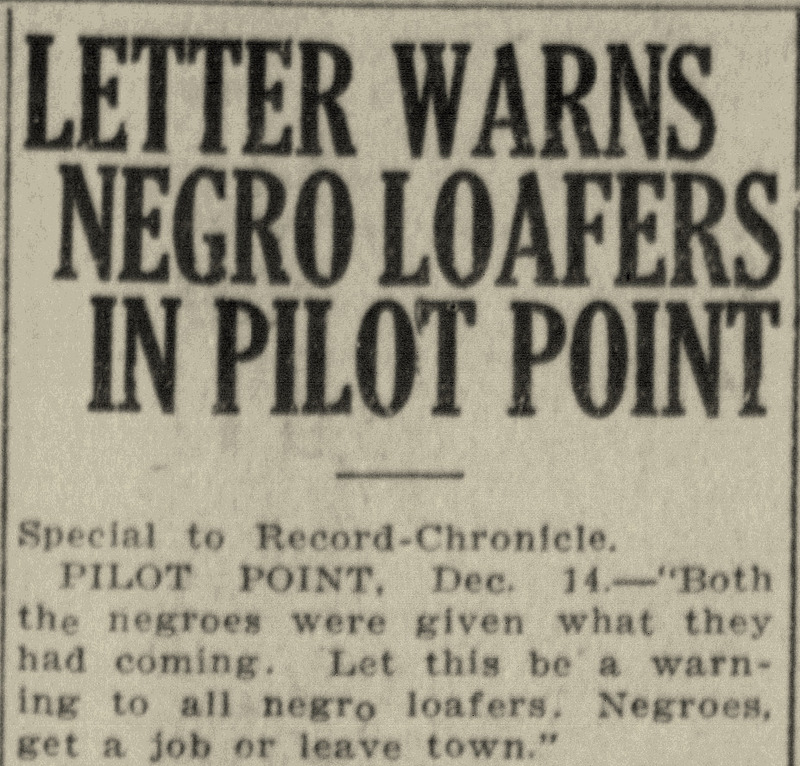

Like the notice left on an envelope in October 1921, another note was found on the door of the Pilot Point Post-Signal by Editor-in-Chief W. J. Miller fourteen months later on the morning of Thursday, December 14, 1922. This time, it was written on plain white paper with a pencil and “bore no signature,” but the implications were clear. “Both the [N]egroes were given what they had coming. Let this be a warning to all [N]egro loafers. Negroes, get a job or leave town.” This message was left by or, more accurately, created by the local Denton County Klan, Klavern 136. Therein, the Klan referenced another pair of Black men from Pilot Point kidnapped, taken from jail after they were accused of a crime, and disappeared by a mob of white men. The series of events which culminated in the lynching of two Black men just after midnight on December 14, 1922, began three days prior at the home of Sam Gertin.

Gertin, a Black long-time resident of Pilot Point, owned a small home at Jefferson and Main Street, on the white side of the downtown square, and a yard where he kept two horses. Gertin’s two sons, Roscoe and Jim, were nearly lynched on March 3, 1910 for causing a disturbance on the front lawn belonging to a white family and the pair spent time in jail for the infraction. On the night of Monday, December 11, 1922, two of Gertin’s horses went missing and he promptly reported the suspected theft to the authorities. The Sheriff’s Department was unable to investigate the crime until Wednesday morning. By the time that Denton County Sheriff James Goode and Deputy Nick Akin arrived to investigate, the bridles, saddles, and blankets from Gertin’s horses were found in the tall grass west of town and the horses themselves reappeared in Gertin’s yard.

While it appeared, the mystery had been solved, Sheriff Goode and Deputy Akin arrested two Black men in connection with the disappearance of Gertin’s horses. They were not charged with a crime. The unnamed Black men were placed in the Pilot Point “calaboose,” a makeshift jail, to be held overnight. Had the men lived to the following morning, they would have heard Sheriff Goode announce that the authorities “did not find sufficient evidence to warrant filing charges.”

On the night of Wednesday, December 13, 1922, like the “flogging” on October 20, 1921, two incarcerated but uncharged Black men were taken from the unguarded Pilot Point jail and lynched by members of the Ku Klux Klan. The following morning, around the same time W. J. Miller found the letter on his door, Pilot Point officers discovered the jail door open and the cell devoid of its prisoners.

Sheriff Goode addressed the reason for the kidnapping indirectly through his argument in favor of their guilt. “We were convinced the [N]egroes arrested got the horses,” Goode extolled, “but we could find no witnesses to support our suspicions.” If law enforcement was unable to convict the men that the Denton County Sheriff was certain were guilty, it meant that the justice system was constrained in such a way as to allow criminals to roam free. This matches the narrative used in the development of the Denton and Gainesville klaverns -- that the system of due process led to free-range criminals -- and with a crime spree reported in the major newspapers of record, this caused public fear. In addition, just two months prior to the lynching, the Denton County Sheriff’s Department reported that they were overwhelmed by criminal activity in the county and incapable of effectively policing it on their own. The lack of evidence, Goode stated, was the reason the sheriff’s department did not “bring [the men] to Denton Wednesday night,” a precaution that would have saved their lives. On the day of the lynching, Sheriff Goode, Deputy Nick Akin, and County Attorney B. W. Boyd were already in Pilot Point on official business outside of the Gertin case. Mr. and Mrs. Joe Burks informed the newspaper that they would be traveling to Denton on December 14, the day of the attack. Sheriff Goode, Deputy Nick Akin, and County Attorney Boyd were back in Denton Thursday morning with no leads on the whereabouts of the men who “disappeared” from the Pilot Point jail.

The story of this “abduction” was incredibly popular on the AP wire. Unlike the Denton Record-Chronicle, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, and Dallas Morning News whose coverage was sparse and referred to the lynching as a mysterious disappearance, newspapers around the country were less inclined to utilize the talking points of the Ku Klux Klan in their reporting. “Two [N]egroes missing at Pilot Point, Tex., are supposed to have been lynched” read an editor’s note in Lincoln, Nebraska; “Lynched Two Prisoners?” asked The Pittsburg Daily Headlight. A publication in Atchison, Kansas, was more direct and printed “Disposed of Two Negroes” as the article’s headline.

In the days and weeks that followed, there was great variation in the content of reports on the lynching of two Black men in Pilot Point, but a singular fact was printed in every article — this has happened before. Each paper printed that “two [N]egroes disappeared from the Pilot Point jail in a similar manner several months ago,” and that of the four men who vanished out of the custody of law enforcement, “no trace of any of them was found.” The event referenced was the “whipping” of two Black teenagers on October 20, 1921 — an event that was never contemporaneously called a lynching. However, in response to the nearly 100 articles on the 1922 extralegal murder in Pilot Point and the persistent comparison to the “whipping” in 1921, it must be considered as more than possible that the two young men who disappeared on Thursday, October 20, 1921 suffered the same fate as those who disappeared on Thursday, December 14, 1922. As the Austin American-Statesman printed, “nothing has been learned as to what became of the two [N]egroes who previously disappeared, officers said, and they are likewise without information as to the whereabouts of the [N]egroes who were arrested yesterday.” It is therefore plausible that all four men were killed in a similar fashion, north of town on the property of Joe B. Burks, in the dark of night.

There are reasons not to trust the official account of these events. The lynching of two men on December 14, 1922 was not called a lynching by any local newspapers. In fact, the only people who directly attributed the event to a Klan lynching were outside of the state of Texas. In contradiction to the reported “whipping” on October 22, 1921, every newspaper account of the December 14, 1922 lynching states that a similar event happened months earlier -- a direct reference to the actions of Klavern 136 on October 20, 1921. If we take these accounts as originating directly from Klan-affiliated newspapers (the Denton Record-Chronicle and the Pilot Point Post-Signal) and therefore as honest to the violence as the Klan desired for it to be a deterrent, then the October 22, 1921 “whipping” should instead be re-categorized as a lynching.

As for the question of whether the October 20, 1921 lynching was lethal, it is apparent through the coverage of the October 20, 1921 disappearance that Klavern 136 desired both for the disappearance of Black bodies to be publicly known and for the end result of their kidnapping to remain mysterious. Were the two teenagers to have lived past their “whipping,” the silence of reporting and investigation would not have been necessary. Men in the mob would have become folk heroes. Conviction for “whipping” a Black criminal, for a first-time white offender, would have resulted in, at most, a suspended sentence by Judge C. R. Pearman. That outcome would also have required felony charges to be filed against the mob of men in a county friendly to racial violence. Actual consequences for a “whipping” were unlikely. Therefore, Denton County Klan members did not seek notoriety for their lynchings because they learned from the attempted prosecution of mob members in nearby Dallas and Fort Worth the importance of unprovable circumstances.

Additionally, the racial violence on October 20, 1921 fits the definition of lynching. The note left behind as a “warning” indicates the violence committed against the young men was done with the intention of terrorizing the Black community, or, more specifically, the goal was to convey a message to Black citizens of Denton County. Second, the teenagers were arrested by Pilot Point police officers and held in jail for an alleged crime that was being investigated by law enforcement. This investigation was ongoing when the Ku Klux Klan removed the prisoners and “applied the lash” as punishment. The actions of the Ku Klux Klan violated the due process rights of the teenagers who were already awaiting charges and were likely too young to be charged with a felony. Also, the perpetrators of this racial violence formed a group to abduct the young men from jail and were never charged with a crime. The day-after-day delay of investigation by Sheriff Goode and resultant lack of action makes clear that the Ku Klux Klan was functionally immune from prosecution in Denton County.