October 20, 1921

According to newspaper reports, two teenagers broke into the home of Sam Norrod on Wednesday, October 19, 1921, while he and his family lay asleep. The young men did not take any property and the only evidence of their presence was the testimony of Mary Norrod, the thirteen-year-old daughter of Sam, who claimed that she saw the young invaders prior to their departure. The following morning, based upon the description provided by Mary Norrod, two Black teenagers were arrested and placed in the Pilot Point jail under suspicion of “immoral conduct involving white women.” This detention was based only upon the allegation that the young men had entered the home of a young white woman rather than any reported interaction between the three teenagers.

The suspects were not initially charged with any crime but remained in jail while the Pilot Point police investigated the previous night’s events. They were from Texarkana, but one of the young men spent his formative years in Pilot Point and had some connection to the town. However, their names were not taken by the police, and so, their identities were listed simply as unknown. To explain the lack of even the most basic investigatory work, the Pilot Point police department asserted that the teenagers were unlikely to spend much time in the Pilot Point jail, as they were likely to be transferred to the Denton County jail upon discovery of incriminating material.

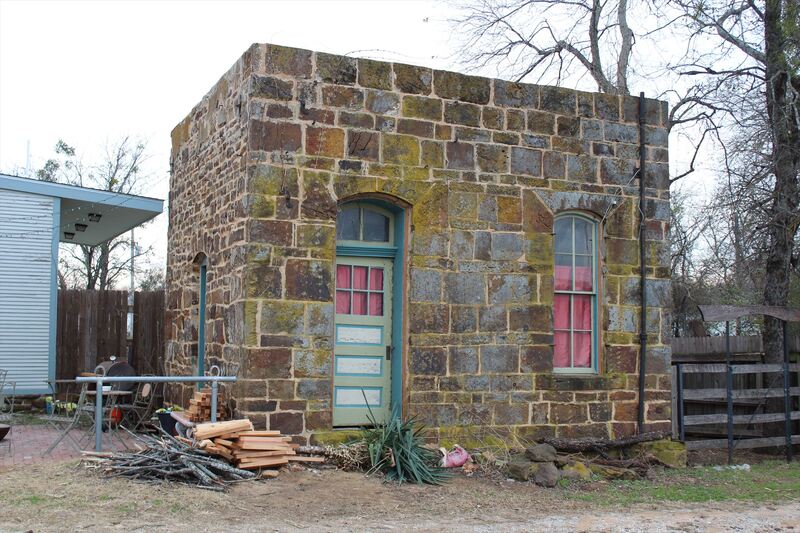

As nightfall of their second day in jail approached, the investigation remained incomplete. Rather than release the two teenagers from custody for lack of sufficient evidence, law enforcement officials prepared for the suspects to spend the night in the remote Pilot Point jail. No guards worked at the six by ten-foot jail, and no law enforcement protected or monitored those incarcerated there at night. At 11pm, three vehicles approached the downtown square and parked near the jail. Several men exited the vehicles, but darkness hid any distinguishing features, such as masks, that may have otherwise been seen by onlookers.

Only minutes after they arrived, the faceless mob entered the unguarded jail and captured the defenseless teens. The prisoners were loaded into one of the cars, which immediately departed for an undisclosed location.

The subsequent events, like the faces of the captors, are hazy. On the same night, twelve vehicles were seen parked in the remote pasture north of town owned by influential Pilot Point banker, Joe B. Burks. In similar accounts of Klan ritual, cars were often parked near a planned event rather than left in a separate location as the headlights were sometimes needed to illuminate the proceedings. In the following morning’s edition of the Denton Record-Chronicle (DRC), the two events were mentioned in the same newspaper article. The DRC was operated by Editor-in-Chief Will C. Edwards, a Klan candidate for the Texas State House of Representatives in 1922 and Lieutenant Governor of Texas in 1924. This established relationship between Edwards and the Ku Klux Klan implies that the article about the kidnapped teens may have functioned as pro-Klan propaganda. While the DRC insisted they were unaware of the location of the young men, it is logical to assume the caravan took the abductees to the field of Joe B. Burks north of town.

While in the custody of the mob, the young men were beaten. The extent to which the teens were brutalized by the faceless assailants beyond “flogging” has been erased from historical records.

Before the mob went home for the night, they made their way to the opposite end of the town square where they tacked a message, written on the back of a white envelope, to the door belonging to the editor of the Pilot Point Post-Signal, W. J. Miller. The note was clearly visible when Miller opened the office door on the morning of Friday, October 21, 1921. Scrawled in pencil across the white paper was a message left for Miller’s dissemination: “Yes we did it -- applied the lash. This should be a warning to all loafers and lawbreakers. K. K. K.”

Approximately 90 minutes later, at12:30am, the Denton County Sheriff, James Goode, was questioned by the press about the mob violence in Pilot Point, but the Sheriff replied that no one had reported the crime. Later that morning, Goode indicated that Deputy Sheriff Decker had other business in Pilot Point that day and would investigate.

It was not until Saturday, October 22, 1921, that Sheriff Goode and County Attorney B. W. Boyd went to Pilot Point to investigate the incident. While there, Goode and Boyd found that the “two young [N]egroes” were taken from jail by “a crowd of men” and given a “severe whipping” on their backs. The Sheriff refused to make a statement beyond these facts until he was able to confer with District Judge Pearman who was “out of the city” until Monday morning.

Map of newspaper coverage of the October 21, 1921 lynching in Pilot Point, Texas.

Despite the national attention created by Associated Press reporting across the nation, local law enforcement still had not acted by Monday, October 24, 1921. The reason for delay was District Judge Pearman’s “busy schedule.” By the next day, all newspaper coverage ceased. According to the many witness accounts and the “investigation” conducted by high-ranking Denton County law enforcement, “no trace of [the young men] was ever found.” The story of racial violence in Pilot Point fell out of public memory, but not out of practice.

What took place in the remote pasture north of town was a lynching. While many of the records that could traditionally tell the story of their ultimate fate have been destroyed, the pattern of violence in Denton County during the rise of the Second Ku Klux Klan is sufficient to establish that, on October 20, 1921, Klavern 136 lynched two young Black men. As such, even in the absence of local reporting or law enforcement evidence, a direct line can be drawn between the events of this case and a nearly identical lynching of two more young black men in December 1922.