Jim Crow Era Mansfield Overview

When Mansfield Independent School District became the first in the state of Texas to have been ordered by a federal court to desegregate and integrate its scholls in 1956. approximately a third of Mansfield’s white-majority population violently defended the town’s oppressive “separate but equal” tradition.[1] Unlike other Texas towns that quietly--albeit grudgingly--desegregated their districts within the decade, pro segregationist Mansfield residents led a protracted act of defiance against desegregation efforts well into the 1960s. To understand Mansfield’s vehement protest against desegregation and integration, one must first place Mansfield’s segregationist culture within the geographic, demographic, and sociopolitical context as it relates to the public education system in the town.

Mansfield, Texas, a Tarrant County town with a population of roughly 1,500 in 1956, was not immune to the sociopolitical trends that permeated in the first half of the twentieth century across the United States, especially in ex-Confederate states. Researcher Robyn Duff Ladino explains, “Situated approximately fifteen miles southeast of Fort Worth, this hamlet was on the fringe of what was known as the Deep South.”[2] During the American Civil War, the town’s property owners contributed to Texas’s Confederate war efforts by having supplied large amounts of commodities produced by the institution of slavery they sought to uphold.[3] As a town with a deep-rooted history of slavery and ties to the Confederacy, Mansfield became a site where discriminatory Jim Crow laws were enforced over the course of several decades to preserve the tight racial hierarchy that white Mansfield residents established at the cost of black residents.

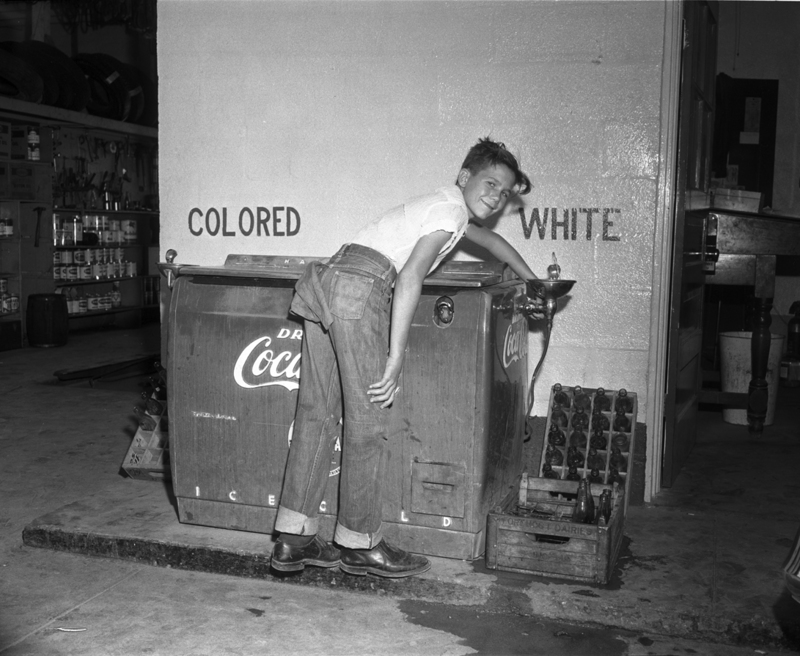

By the 1950s, these Jim Crow laws and customs directed the daily lives of the approximately 1,500 town residents, 350 of whom were black and relegated to the west side of the segregated town.[4] Long-time resident Jossie Brooks explained that when she arrived to Mansfield in the 1940s, the west side seemed like a “deserted place,” and that roads in that part of town were not paved until the late 1990s and early 2000s. The only church in town that black residents were allowed to attend was Bethlehem Baptist Church in the west side. In addition, Brooks explained that black residents were required to enter grocery stores through the back door and were forced to watch movies in the upper balcony of the local Farr Best Movie Theater when they had the means to spend their income at those and similar establishments, which was rare.[5] When black residents were seen by local police in areas reserved exclusively for whites they were subject to excessive harassment, according to one black Mansfield resident.[6] Moreover, segregation not only restricted the lived experiences of black Mansfield residents, but their final resting place as well. The local cemetery assigned black residents burial plots to the north side of the space and white burial plots that contain ex-Confederate soldiers and ex-slave owners to the south side, with a short chain link fence dividing the two areas.

Despite the segregated churches, restaurants, and other social establishments that reminded black residents of their second-class citizenship, some white Mansfield residents insisted that race relations were “good,” and therefore the town did not merit integration.[7] Black Mansfieldians disagreed. In order to implement the characteristics of an equal society within their city limits, many black residents set their sights on improving the educational experiences of themselves and of their children.

Keeping with the custom of “separate but equal” facilities in the middle 1950s, Mansfield ISD separated their 700 white students from the district’s sixty black students who attended the Mansfield Colored School up to the ninth grade. Located in the west side of town, the Colored School was made up of “two long shabby barracks-style buildings placed lengthwise, side by side.”[8] When they reached the ninth grade, black students who wanted to continue their education were bused to Fort Worth to attend I.M. Terrell High School. Journalist Bob Ray Sanders described the journey that black high school students embarked on each day on their way to and from school. With their parents having financed their transportation, black students first took a Continental Trailways bus from Mansfield to downtown Fort Worth. Once in Fort Worth, students either walked or took a second bus to transport them to I.M. Terrell, then repeated the trip in reverse to go home. This made for long days and participation in extracurricular activities difficult.[9] Mrs. Brooks recalls the countless trips her brothers took from Mansfield to Fort Worth, and indicated that students were regularly away from the home for about twelve hours each day.[10]

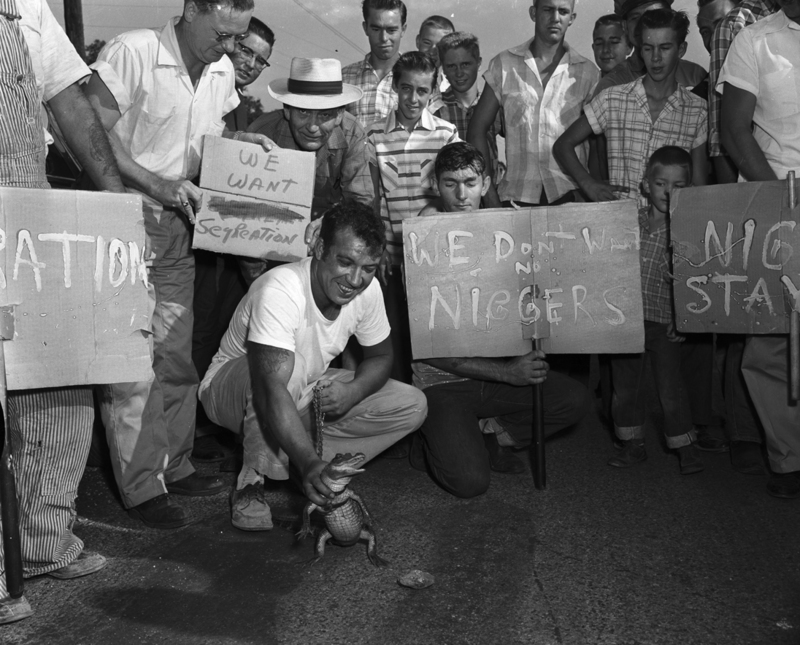

According to white Mansfield residents who sought the continued segregation of the town’s public schools, race relations did not become tense until out-of-state organizations, namely the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, "instigated" turbulence in the town and “forced integration down white residents’ throats.”[11] Ignoring the fact that the NAACP-affiliated civil rights activists who initiated the desegregation suit were from the town, segregationists in Mansfield and across Texas argued conveniently that the federal mandate for the desegregation of public schools was an infringement of state’s rights. Pro-segregation protests became violent. Although violence is often defined by acts of physical assault, violence begins with the threat of such behavior. Mansfield is a town with a history of violence that precedes the integration protests of 1956. One instance involving local activist T. M. Moody ended with Anglo school board members threatening him with lynching after Moody insisted that black Mansfield students receive new textbooks.[12] In the Deep South, especially in Texas, lynching and the threat of lynching carried with it a legacy of mob and state-sponsored violence against black residents. Between 1885 and 1942, nearly 340 black Texans were lynched. One of the most lynching-prone areas during this period was in northeast Texas.[13]

As a town located on the fringes of the Confederate South, Mansfield replicated the attitudes, arguments, and ironies that manifested across the region in states like Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia in the 1950s and 1960s. Racist Anglo residents resorted to mob violence and the threat of mob violence when “local custom” was scrutinized, local custom that entailed the separation of black and white students in schools and the humiliating routines that black residents were forced to abide by when they desired or required access to the facilities in Mansfield. Since this “local custom” was upheld by the state apparatus in places like Mansfield and throughout the Deep South for over a century, local residents’ defense of Jim Crow segregation naturally relied on violence and the threat of physical force, as demonstrated by the Integration Crisis at Mansfield High School in 1956.

[1] Robyn Duff Ladino, Desegregating Texas Schools: Eisenhower, Shivers, and the Crisis at Mansfield High (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), 3; “Mansfield School Desegregation Incident,” The Handbook of Texas, accessed April 19, 2015, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/jcm02.

[2] Duff Ladino, Desegregating Texas Schools, 3.

[3] Duff Ladino, Desegregating Texas Schools, 3.

[4] “Mansfield School Desegregation Incident,” The Handbook of Texas, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/jcm02.

[5] Jossie Brooks, interview by Katie McAnally and Moises A. Gurrola, April 9, 2015, University of North Texas Oral History Program, Denton, Texas.

[6] Stan Solamillo, “A Society of Meanness,” The Mansfield African American Oral History Project, Mansfield Public Library, Mansfield, Texas, page 20-21.

[7] Duff Ladino, Desegregating Texas Schools, 5.

[8] Duff Ladino, Desegregating Texas Schools, 6.

[9] Bob Ray Sanders, interview by Miles Davison, February 27, 2013, Civil Rights in Black and Brown Oral History Project, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, Texas.

[10] Jossie Brooks, interview by Katie McAnally and Moises A. Gurrola, April 9, 2015, University of North Texas Oral History Program, Denton, Texas.

[11] “Mansfield School Mob Roughs up 2,” The Austin American, September 1, 1956; ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY MEGAN CITED HERE WITH CONTENT EDITED TO ACCURATE WORDING.

[12] Solamillo, “Courage, Grace, and Tenacity,” The Mansfield African American Oral History Project, Mansfield Public Library, Mansfield, Texas, 32-33.

[13] “Lynching,” The Handbook of Texas, accessed April 19, 2015, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/jgl01.