Allan Shivers

Allan Shivers was born on October 5, 1907, in Lufkin, Texas to a poor East Texas family. After graduating from Port Arthur High School in 1931, Shivers attended the University of Texas and graduated in 1934 with a law degree. After passing the state bar exam, Shivers worked in a private law practice until 1936, when he was elected as a Democrat to the state senate. At the time Shivers became the youngest serving state senator at the age of twenty-seven. In 1937 he married Marialice Shary, the daughter of a wealthy family, which offered an avenue for an ambitious political career.[1]

In 1946, he was elected state lieutenant governor and was reelected two years later. During his tenure as lieutenant governor Shivers implemented the practice of appointing senators to specific committees and worked closely with Democratic Governor Beauford H. Jester. Upon Jester’s death in 1949, Shivers assumed the role of governor and held the position for the next eight years. As governor, Shivers was known for his competitive personality as well as his influence on the state senate and court decisions.[2]

In the gubernatorial race of 1954 Shivers took a more vocal stance on keeping Texas schools segregated and politicized the issue throughout his campaign. When discussing segregation on the campaign trail, Shivers said, “We are going to keep the system that we know is best. No law, no court, can wreck what God has made. Nobody can pass a law and change it.”[6] In addition, he began to attack his primary opponent, Yarbrough, on the issue of segregation and claimed that Yarborough and the NAACP had similar goals. Yarborough responded to the accusations by saying he was against, “the commingling of races in public schools.”[7] Shivers won the run-off primary against Yarborough and was reelected to the position of Texas governor for an unprecedented third term. During the campaign, Shivers adopted a party platform that denounced the Supreme Court’s Brown I decision as an “unwarranted invasion of state’s rights.”[

On July 27, 1955, Shivers appointed a forty-member committee to study and assess the segregation issues Texas would face in the wake of the Brown I and Brown II decisions. The responsibility of the committee was to determine whether state legislation was needed and whether both races were motivated to attend desegregated public schools.[9] Later that year the Texas Supreme Court ruled that the laws on segregation were invalidated by the United States Supreme Court’s decisions. Shivers responded by saying, “In the light of these decisions, no school district should feel compelled to take hasty or unnecessary action.”[10] Shivers directed his statement towards local school boards who hoped to maintain segregation, despite the court rulings, and further stall the integration process.

In January 1956, Shivers wrote to Virginia Governor Thomas B. Stanley, requesting a copy of the state’s interposition resolution.[11] After receiving the resolution Shivers sent the document to the Texas Advisory Committee on Segregation in Public Schools as it began to circulate among lawmakers. During February and March of 1956, state lawmakers, organizations and citizens signed petitions that requested the governor to call a special session, in order to address the issues of state’s rights and interposition. However by this time Shivers was aware of the break-down in his political machine, and in March 1956 announced he would not seek a fourth term. Although power of the “Shivercrats” faction was waning, Shivers backed Price Daniel as governor and continued his cause for interposition. In September 1956, Shivers came out again in support of Eisenhower. By the beginning of the new school in September, over 100 school districts in Texas were desegregated or in the process of desegregating. However, in the town of Mansfield, Texas, the segregation issue escalated to national attention and demanded action from the Governor.

Due to the heightened tension in Mansfield and the public outcry for action, Shivers responded to the situation. On August 31, 1956, he released a press memorandum acknowledging L. Clifford Davis’ request for law enforcement and aid. Shivers stated:

Law and order must be maintained in Mansfield, as in the rest of Texas.

Neither the Governor’s Office nor the Department of Public Safety has received any request from the Tarrant County sheriff for assistance. When and of such a request is made, it will be honored.

I am certainly not inclined to move state officers into Mansfield at the call of a lawyer affiliated with the National Association for Advancement of Colored People, whose premature and unwise efforts have created this unfortunate situation at Mansfield.[12]

Later that day, Shivers released a second memorandum announcing a three-step plan for dealing with the Mansfield situation. The first step was to use the powers of governor to enforce laws and instructed Colonel Garrison to send Texas Rangers to Mansfield to cooperate with local authorities in preserving the peace. The second action stated that Shivers was in contact with O. C. Rawdon and urged the school board to transfer out of the district any students, white or black, whose attendance or attempts to attend Mansfield High School would incite violence. Shivers further stated that the action would be in line with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision concerning Autherine Lucy’s efforts to integrate the University of Alabama. The final action was instructions to Colonel Garrison that the Texas Rangers arrest anyone whose actions would threaten the peace at Mansfield.[13] As a result, the governor’s plan ensured that segregation would continue in Mansfield High School by not offering escorts for African American students who attempted to enroll.

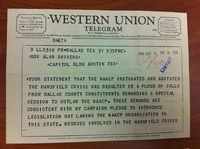

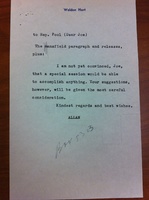

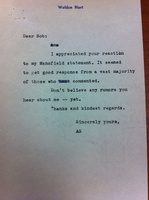

On September 6, Shivers held a news conference and declared his actions in Mansfield were successful in restoring order and that the crisis in Mansfield was over. He went on to say the blame of the turmoil was due to “paid agitators,” which he indirectly attributed to the actions of the NAACP. Western Union telegrams flooded Shivers’ office stating that he should be commended for his actions, while others called for the NAACP organization to be “thrown out of the state for attempting to create riots.”[14] At the end of his term, Shivers left the governor’s office in good favor. After his departure, Texas Attorney General Shepperd and the new Governor, Price Daniel, continued his policies on segregation. During the 1957 Little Rock Crisis, Shivers visited President Eisenhower and Attorney General Brownell at the president’s vacation home in Newport, Rhode Island. The former Texas governor advised the executive branch on Arkansas Governor Orval Fabus and Eisenhower deemed federal intervention necessary.

[1] Ben H. Procter, "SHIVERS, ROBERT ALLAN," Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fsh40), accessed April 29, 2015. Uploaded on June 15, 2010. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Robyn Duff Ladino, Desegregating Texas Schools: Eisenhower, Shivers, and the crisis at Mansfield High (University of Texas Press, Austin: 1996), 36.

[5] Ibid., 37.

[6] Ibid., 38.

[7] Ibid., 38.

[8] Ibid., 39.

[9] Ibid., 42.

[10] Ibid., 42.

[11] Governor Allan Shivers, Press Memorandum, Office of the Governor, January 27, 1956, Shivers Papers, Folder: Segregation 1956- Mansfield, Box 1977/81-532, Texas State Archives.

[12] Governor Allan Shivers, Press Memorandum, Office of the Governor, August 31, 1956, Shivers Papers, Folder: Segregation 1956- Mansfield, Box 1977/81-532, Texas State Archives.

[13] Governor Allan Shivers, Press Memorandum, Office of the Governor, Statement, August 31, 1956, Shivers Papers, Folder: Segregation 1956- Mansfield, Box 1977/81-532, Texas State Archives.

[14] State Representative Joe Pool to Governor Allan Shivers, Telegram, August 31, 1956, Shivers Papers, Folder: Segregation 1956- Mansfield, Box 1977/81-532, Texas State Archives.