Agriculture in Texas and Denton County

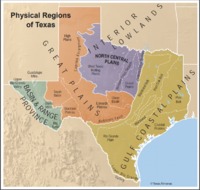

Pilot Point, residing in Denton County in North-Central Texas, lies in the North Central Plains region of Texas. This geographic region includes sections of cross timbers and prairies, both of which can be found in Denton County. The Grand Prairie and Blackland Prairie regions of the county contain rich black soil which is beneficial to growing staple crops and raising livestock, and the cross timber regions are better suited for the growth of fruits and vegetables.

Prior to the Civil War, cattle and cotton were integral pieces of Texas’ economy with cotton being the primary export and cattle being the second. In 1860, the value of cattle in Texas was $43 million and Texans produced more than 431,000 bales of cotton. Most agriculture took place on small, subsistence farms.

After the Civil War, slavery became replaced by tenant farming. Tenant farming is a system that includes cash tenants, share tenants, and sharecroppers. Cash tenants would pay annual cash rents to a land owner in order to work the farm. Share tenants generally “provided their own seed, work animals, and equipment and paid the land owner one-fourth of the cotton and one-third of the corn as rent,” though the arrangements could vary. Sharecroppers typically “provided only their own labor and received the proceeds of half of the cotton crop.” Tenant farmers owned no land and typically had few, if any, cash resources. Due to the lack of funds, tenants often turned to local merchants to borrow fund to secure tools, equipment, seeds, and other necessities. In return, the tenant farmer agreed to a chattel mortgage on his crops and/or livestock. However, since the merchants kept the ledgers and charged higher prices for goods sold on credit, tenant farmers tended to only break even, thus perpetuating the cycle further. Tenant farmers would be both black and white, however by 1880 white tenant farmers far outnumbered black tenant farmers in Texas.

Despite the hardships associated with tenant farming, the number of farms in Texas grew following the Civil War. In 1870 there were approximately 61,000 farms, by 1880 the number grew to 174,000, and grew even more to 350,000 by 1900. Due to the growth in commercial production and marketing, farming and ranching continued to expand. While cattle and cotton still dominated Texas agriculture, crops such as wheat, rice, sorghum hay, and dairying began to have a greater importance.

Denton County began to grow following the Civil War and its population increased from 4,780 in 1860 to 7,251 in 1870 and 18,143 in 1880. The number of farms increased in the county from 566 in 1870 to 2356 in 1880. In 1870 Denton county primarily produced wheat, Indian corn, oats, and sweet potatoes, but also grew rye, barley, tobacco, cotton, and potatoes. By 1880 the production of wheat increased by nearly 300%, Indian corn by over 200%, and oats by approximately 175%. Additionally, the production of oats began its steady increase with an output of over 100,000 bushels and cotton became prominent with almost 12,000 bales produced.

While agriculture began its growth, the production of livestock began to decline in importance as crop production took over a majority of the land — 89% in 1920. In 1870, Denton county had approximately 37,000 head of cattle, this number peaked in 1890 with around 60,000 head, but by 1920 had declined to approximately 26,500. A similar trend can be seen with pigs in the county. Prior to the Civil War farmers in Texas primarily used teams of oxen for plowing fields, however afterwards mules became much more prevalent for these purposes. This trend can be seen in Denton county as the number of asses and mules increased from just over 300 in 1870, to over 1,800 in 1880, and almost 9,000 in 1920.

During the first two decades of the twentieth century, an increased demand for agricultural products drove prices up and brought prosperity back to Texas farmers. During this period, Texas farms increased the number of cultivated acres on farms from fifteen to twenty-five million. Additionally, cotton production increased from 3.4 to 4.3 million bales, corn stabilized at approximately 100 million bushels, and the value of livestock increased from $240 to $590 billion. Wheat emerged as a major export by 1900 with its production and milling centered in north central Texas. During these two decades, livestock production (namely cattle, sheep, and goats) covered approximately 70% of the state and crop production covered 17.5%. On the portion of land dedicated to crop production, cotton took up approximately 60% of the cultivated acreage, crops such as corn, sorghum, and wheat covered the other 40%.

Denton County was “ideal for wheat culture” and between 1890 and 1920 the county ranked either first or second in the state falling behind Collin county. Acreage of wheat in Denton county grew from just over 12,000 acres in 1880 to almost 100,000 acres in 1920, an increase of over 700%. In 1920 alone, Denton county produced over one million bushels of corn. Cotton began a steady increase in production and went from just over 12,000 in 1890 to over 33,000 in 1920, a total increase of approximately 175%. In 1920, the value of all crops produced in Denton county was over thirteen million dollars and ranked 17th in the state.

During the 1920s, farmers experienced various hardships. The agricultural crisis of 1920-21 began when postwar commodity surpluses caused a sharp decline the price of crops. Farmers sought various solutions, but ultimately the agricultural issues only contributed the economic disaster that was to come — the Great Depression. The prices of crops bottomed out, for example what went from $2.04 a bushel to 33¢ and total cotton sales plummeted from $376 to $140 million between 1920 and 1932. Despite this, the number of farms in Texas grew from 436,038 in 1920 to 495,489 in 1930, and the total acreage of cropland grew by 3.5 million acres. Crops such as wheat and cotton were planted in even greater acreage, only contributing to the surpluses — cotton increased from 12.9 to 16.6 million acres and wheat increased from 2.4 to 4.7 million acres. Between the Dust Bowl and these developments, crop production virtually stopped in some areas of the state and rural poverty spread across the state. It would not be until the implementation of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs focused on farming and agriculture that these issues would be remedied, and the state’s agricultural system would have long-term changes.

Following 1920, the total value of crops in Denton county dropped to 8.7 million in 1925, approximately a 35% decrease from 1920. The value of crops continued to fall, and in 1930 Denton county’s production was valued at only 5.5 million, a 37% decrease from 1925. Additionally, the value of livestock dropped by approximately 40% between 1920 and 1930. The number of farms fell from 4200 in 1920 to 3963 in 1930, and the value of farms fell by almost 45% in the same timeframe. The number of farm owners during this time fell by over 400, the former owners either turned to tenant farming or left agriculture all together. During the New Deal, Denton farmers took advantage of New Deal programs like the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA), the Soil Conservation Service (SCS), and various other programs. In 1933 alone, Denton farmers were paid approximately $335,000 for destroying their cotton crops and nearly $45,000 for not planting wheat through the AAA. Denton county benefitted from FDR’s New Deal programs, and by the end of the New Deal their conditions were improved.

Citations:

"Physical Regions of Texas," Texas Almanac, https://texasalmanac.com.; Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, "Agriculture," "Denton County," http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook; Randolph Campbell, Gone to Texas: A History of the Lone Star State, 2nd edition (Oxford, Oxford: University Press, 2012).; Steven Manson, Jonathan Schroeder, David Van Riper, and Steven Ruggles. IPUMS National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 12.0 [Database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. 2017. http://doi.org/10.18128/D050.V12.; Rodney J. Walter, "The Economic History of Denton County, Texas, 1900-1950," (MA thesis, University of North Texas, 1969).