Church & Education

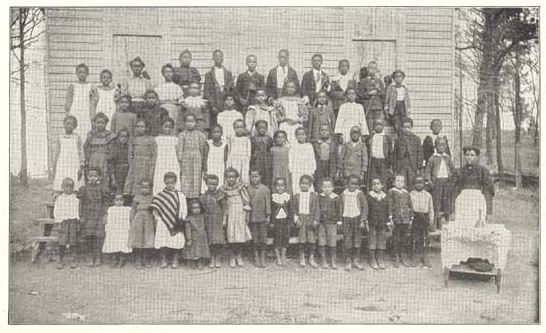

Aside from the desire for former slaves to form local autonomous churches, they also wanted education for their community. Following the Civil War, before the establishment of public school systems in the South, churches were used for teaching and as a gathering place for community activities. The ministers of local African American churches were often prominent leaders of the community who performed other duties besides preaching, and might serve as community leaders, teachers, and business strategists. For example, C.C. Trimble and W.P, Huntley of Pilot Point, Texas, served as ministers for County Line Baptist Church and other churches, and as educators for the African American school in town during the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Church organizations, mostly from the North, such as the American Missionary Association, Baptist-led; American Baptist Associations, Baptist-led; Freedmen Aids Society, Methodist and Baptist-led; and more promoted education for southern black children and freedmen after the Civil War. Through the assistance of these organizations, many of the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) were organized. Between 1870 and 1930, six HBCU’s were directly sponsored by church denominations, mostly predominant African American denominations, including; Texas College, Tyler; Huston–Tillotson University, Austin; Wiley College, Marshall; Jarvis Christian College, Hawkins; Paul Quinn, Dallas (formally Waco); St. Philips College, San Antonio. Throughout the rest of nineteenth century and early twentieth century, education became the center of discussion for African American church organizations. Church conferences and other church-affiliated organizations such as the Baptist Youth Peoples Union (BYPU), YMCA, and the Sunday school movement formed to help the African American youth develop leadership skills and further education. In addition, the predominantly white Methodist Protestant Church continued to fund the Freedmen’s Society into the late nineteenth century.

“Negro Baptist Young Peoples Union Holds Its Annual Meeting at Greenville,” Dallas Morning News (Dallas, Tex), Vol.16 , No. 258, Ed.1, June 15, 1901, newspaper, Dallas Public Library, Dallas, Texas; “North Texas Negro Teachers: List of Papers Read At Meeting of Association at Sherman,” Dallas Morning News (Dallas, Tex), Vol.22 , No. 64, Ed.1, December 2, 1906, newspaper, Dallas Public Library, Dallas, Texas; Methodist Episcopal Church, Journal and Minutes of the Fourth Session of the West Texas Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church Held at San Antonio, Texas, November 29, 1876 (Dallas: Commercial Steam Printing House, 1877), 9-12.