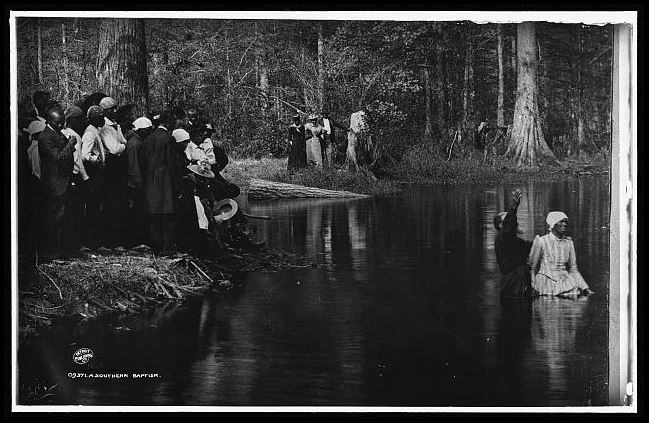

Church: A Haven for the Community

Black southerners lived in an extremely vulnerable and dangerous position in Jim Crow society during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Through segregation, disfranchisement, and lynching violence, white southerners successfully branded blacks as second-class citizens. Often black southerners were forced to mask their frustrations from whites, as terror, harassment, or death often lurked around the corner. Many black southerners viewed churches in their community as safe places where they could express their frustrations and sorrows that accompanied life in Jim Crow society.

"This was the one place where the Negroes in my community could be free and relax from the toil and oppression of the week. Among themselves they were free to show off and feel important"

-Benjamin Mays

Although many black southerners depended on church for spiritual agency and as a guiding force in their lives, church members were not always unified in southern churches. By the late nineteenth century, generational differences regarding worship services and other church activities became more apparent in southern black communities. Emerging black leaders such as Booker T. Washington and Ida Wells expressed their skepticism with southern black ministers and their worshiping styles. For instance, Wells argued, that three-fourths of the Baptist ministers and two-thirds of the Methodist were unfit, either mentally or morally, or both. In addition, Washington was known for making anti-clerical jokes during his speeches. Other members of black rural southern congregations expressed their concerns about black preachers being competent enough to lead a congregation. For instance, a young black man from Arkansas expressed his concerns in 1894 with church preachers. “who could neither read or write, while trying to govern a large congregation.” Despite the influential position that rural black southern churches were in, there were still disagreements among congregation members on how to lead the church community.

Citations:Leon Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Knopf, 1998), 150, 496; Edward L. Ayers, Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press) 164.