Segregation in Church

With emancipation, most white southerners seemed happy that black southerners formed their own congregations. By 1870, most black and white southerners worshipped with members of their own race, as Martin Luther King Jr. put it, “the most segregated hour of Christian America is eleven o’clock on Sunday mornings.” While there is documented evidence of black and white southerners attempting to form biracial congregations, these were rare. For example, in 1881 the white Presbyterian Church of Blacksburg, North Carolina decided to offer outreach preaching services for the local black population once a month at night; however, despite high attendance, these worship services soon ceased. One of the white preachers expressed, "the colored preachers thought we were infringing on their rights." Paige Patterson, a leader in the predominantly white Southern Baptist Convention: "When it comes to rhetoric, the best Anglo preachers on their best days don't preach as well as a good black preacher on his worst day.”

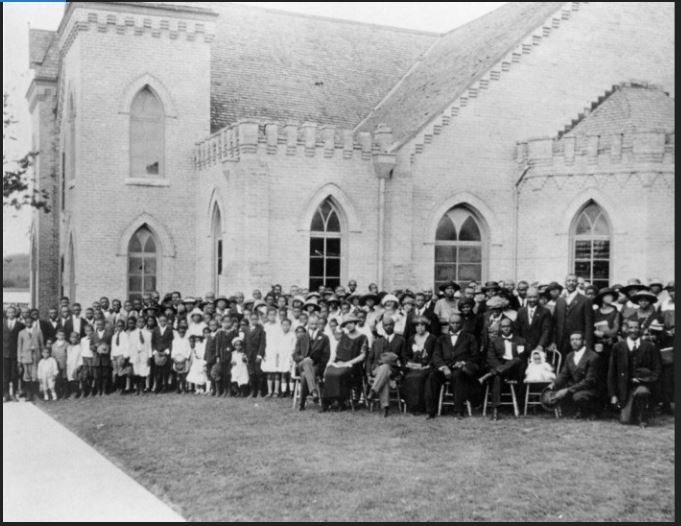

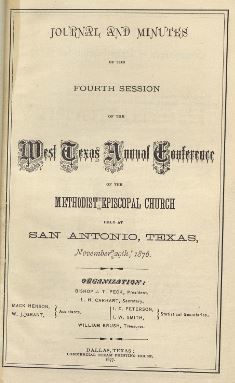

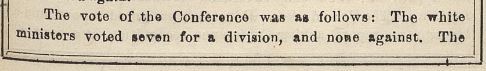

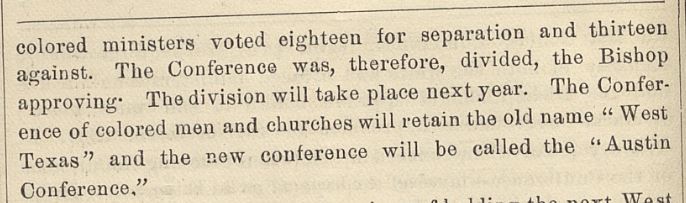

In 1895, the Southern Baptist Convention agreed to aid institutions that trained black ministers, although the program was discontinued five years later. Although the Southern Baptist Convention acknowledged that there were racial divisions within Southern Baptist churches, congregations remained racially segregated. Furthermore, the ME Church in Texas decided to hold separate conferences for black and white members after 1876. Although some black ministers were in favor of having a separate conference for black members, this separation demonstrates how racially segregated churches were in the South. Ultimately, blacks were uncomfortable accepting aid from white churches out of fear of losing autonomy. Whites were uncomfortable with educating blacks, which black churches played a major role in educational promotion. With these circumstances, it was very difficult to form bi-racial congregations in the South in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Above: In 1876, during the West Texas Conference of Methodist Episcopal Church, a predominatly white Church decided to hold separate state conferences for African American and white Methodist Episcopal members.

Citations:

Edward Ayers, Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007) 160-165; James C. Klagge, “The Most Segregated Hour in America?” Virginia Tech, College of Liberal Arts and Human Sciences. http://www.phil.vt.edu/JKlagge/ConductorChurch.htm (accessed April 20, 2018); Methodist Episcopal Church, Journal and Minutes of the Fourth Session of the West Texas Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church Held at San Antonio, Texas, November 29, 1876 (Dallas: Commercial Steam Printing House, 1877), 9-12.