African American Church Denominations

Since the early nineteenth century, church denominations in the United States became increasingly divided by race, especially between whites and African Americans. Evidence of organized racial divisions among church denominations occurred when the African Episcopal Methodist (AME) Church and the African Episcopal Methodist (AME) Zion Church formed separate denominations from the Methodist Episcopal (ME) Church.

The AME and AME Zion Churches separated from the ME Church in 1816 and 1821 for similar reasons. African American found themselves in the minority of the ME Church, and felt that their interests were not being represented in the white dominated church. For instance, all the presiding elders and preachers in positions of leadership were all white men. Additionally, African American minsters were sometimes barred from attending or delivering speeches at the ME conferences.

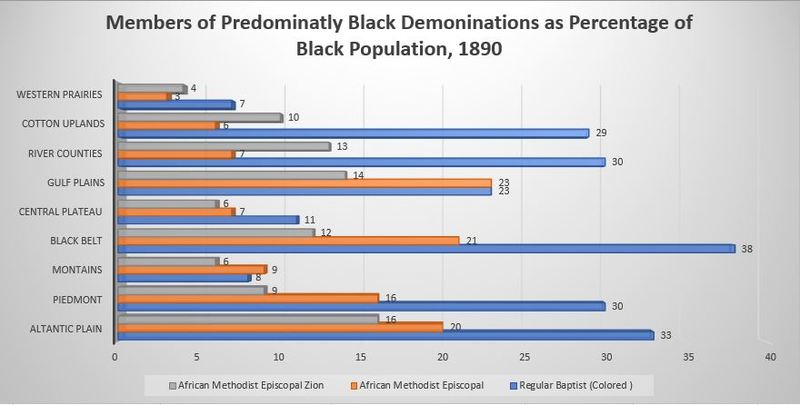

In 1891, decades after the AME separation, leaders of the church believed that the separation “has been beneficial to the man of color by giving him an independence of character which he could neither hope for nor attain unto, if he had remained as the ecclesiastical vassal of his white brethren.” After the Civil War ended, the AME and AME Zion Churches were able to expand outside their New England homebased into the South where four million freedmen and women resided. Former slaves were eager to start their own congregations to achieve a sense of independence. In addition, white southerners after the Civil War were not keen for former slaves to join white-denominated churches. Former slaves thus formed the Colored Methodist Episcopal (CME) Church in the South. Following emancipation, it was important for former slaves to form decentralized congregations to meet their local needs and interests. This is one reason Baptist churches proved appealing to African Americans, since the Baptist churches generally encouraged local autonomy. By 1890, there were over 1.3 Million black Baptists in the South, nearly three times as other black denominations.

Citations: Daniel Alexander Payne, History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church: Electronic Edition, eds. C.S. Smith, Documenting the American South, University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2001, 9-12. http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/payne/payne.html#p9 (accessed April 20, 2018); Edward L. Ayers, The Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 160, 504; John Buesher,“Baptist Origins,” Teachinghistory.org. http://teachinghistory.org/history-content/ask-a-historian/22329